Bellocq's Women by Peter Everett

Description

More

Less

In 1912, in Storyville, the notorious red-light district of New Orleans, a photographer named E. J. Bellocq took a series of photographs of the women who worked in the brothels. Rediscovered in the 1950s, Bellocq's photographs have become famous, but the man himself remains a mystery.In Bellocq's Women, Peter Everett performs as remarkable a feat of fictional reconstruction as he did in Matisse's War and The Voyages of Alfred Wallis. All we have of Bellocq are his photographs and a few fragmentary memories; in this extraordinary novel Everett not only brings the photographer to life - and with him his strange, tortured relationship with his mother and two young girls, one his landlady's daughter, the other a child whore - but also his world - the opium dens and bar rooms of New Orleans and the whore houses with their surreal combination of violence and homeliness.

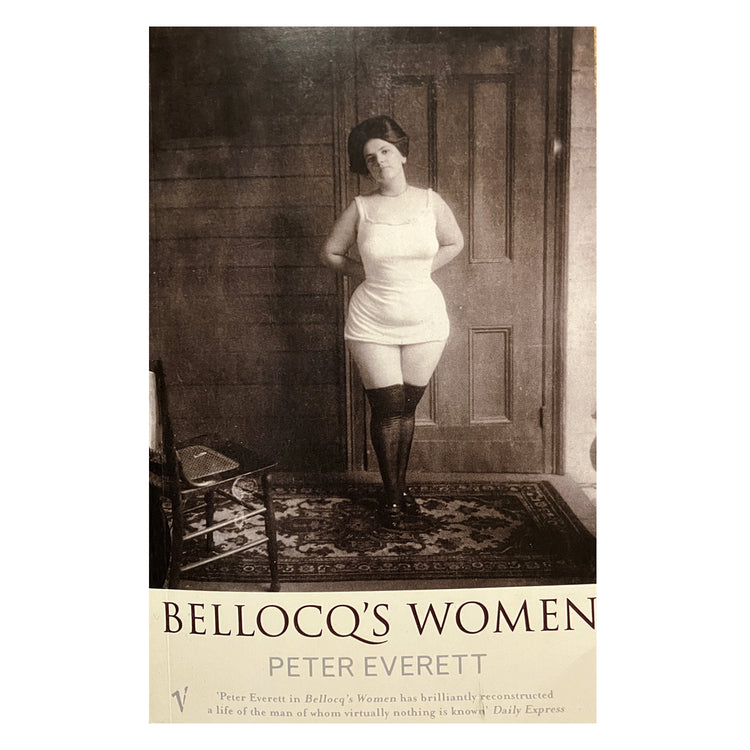

The ninth and final novel by Peter Everett who died in 1999, was inspired by a series of portraits of prostitutes taken by EJ Bellocq in 1912 in the red-light district of New Orleans. The photographs, undiscovered until the 1950s, capture the lush surroundings of Storyville brothels, which employed 2,000 women, made millions each year and were closed down by the city council shortly after the photos were taken. Bellocq's image of a young, frank curvaceous woman on the book's cover attest that his eye "caught the very bloom on things." Although little is known of Bellocq, Everett builds a quirky and compelling account of what drew him to his subjects, beginning with his fascination with a murder trial in 1889, which involved the sexual abuse of a young girl. Everett retains a tone of cool reportage even when Bellocq visits his first brothel and fails to lose his virginity. "Ever afterwards, it was the girl's frail hands washing his penis that Bellocq brought to mind when he was playing with himself." The opening chapter is slightly jerky and distanced but the novel comes quickly into sharper focus as Bellocq sets off to Mexico to escape a domineering, religious mother.

Everett subtly conjures the light and shade that frame scenes in Bellocq's mind: "The light from an open door cast a woman's shadow", beautifully suggests the photographer's loneliness and foreshadows his subsequent passion. Years later, the lights dying out on a riverboat and the smell of dead geraniums recall the closing of the brothels and the end of Bellocq's controlling force. There is something naive, patient and non-judgmental about the Bellocq Everett creates. One admirer comments that "he treated all the women the same way. They all seemed to live in an Inner Light--none was any more beautiful or ugly than another." With his fine eye for period detail, for evincing the smells and sounds of New Orleans, Everett makes the world of Bellocq fantastically present. Bellocq's relationships with women were unconventional, respectful and gently voyeuristic. Everett proposes that his daring, erotic photographs mark the most decisive and successful moments of his life--the portraits being the only way he could really "have" women in any lasting manner at all. --Cherry Smyth

Description

In 1912, in Storyville, the notorious red-light district of New Orleans, a photographer named E. J. Bellocq took a series of photographs of the women who worked in the brothels. Rediscovered in the 1950s, Bellocq's photographs have become famous, but the man himself remains a mystery.In Bellocq's Women, Peter Everett performs as remarkable a feat of fictional reconstruction as he did in Matisse's War and The Voyages of Alfred Wallis. All we have of Bellocq are his photographs and a few fragmentary memories; in this extraordinary novel Everett not only brings the photographer to life - and with him his strange, tortured relationship with his mother and two young girls, one his landlady's daughter, the other a child whore - but also his world - the opium dens and bar rooms of New Orleans and the whore houses with their surreal combination of violence and homeliness.

The ninth and final novel by Peter Everett who died in 1999, was inspired by a series of portraits of prostitutes taken by EJ Bellocq in 1912 in the red-light district of New Orleans. The photographs, undiscovered until the 1950s, capture the lush surroundings of Storyville brothels, which employed 2,000 women, made millions each year and were closed down by the city council shortly after the photos were taken. Bellocq's image of a young, frank curvaceous woman on the book's cover attest that his eye "caught the very bloom on things." Although little is known of Bellocq, Everett builds a quirky and compelling account of what drew him to his subjects, beginning with his fascination with a murder trial in 1889, which involved the sexual abuse of a young girl. Everett retains a tone of cool reportage even when Bellocq visits his first brothel and fails to lose his virginity. "Ever afterwards, it was the girl's frail hands washing his penis that Bellocq brought to mind when he was playing with himself." The opening chapter is slightly jerky and distanced but the novel comes quickly into sharper focus as Bellocq sets off to Mexico to escape a domineering, religious mother.

Everett subtly conjures the light and shade that frame scenes in Bellocq's mind: "The light from an open door cast a woman's shadow", beautifully suggests the photographer's loneliness and foreshadows his subsequent passion. Years later, the lights dying out on a riverboat and the smell of dead geraniums recall the closing of the brothels and the end of Bellocq's controlling force. There is something naive, patient and non-judgmental about the Bellocq Everett creates. One admirer comments that "he treated all the women the same way. They all seemed to live in an Inner Light--none was any more beautiful or ugly than another." With his fine eye for period detail, for evincing the smells and sounds of New Orleans, Everett makes the world of Bellocq fantastically present. Bellocq's relationships with women were unconventional, respectful and gently voyeuristic. Everett proposes that his daring, erotic photographs mark the most decisive and successful moments of his life--the portraits being the only way he could really "have" women in any lasting manner at all. --Cherry Smyth

You May Also Like